Irish Independent Walk of the Week Christopher Somerville

Irish Independent Walk of the Week Christopher Somerville

9 April 2011

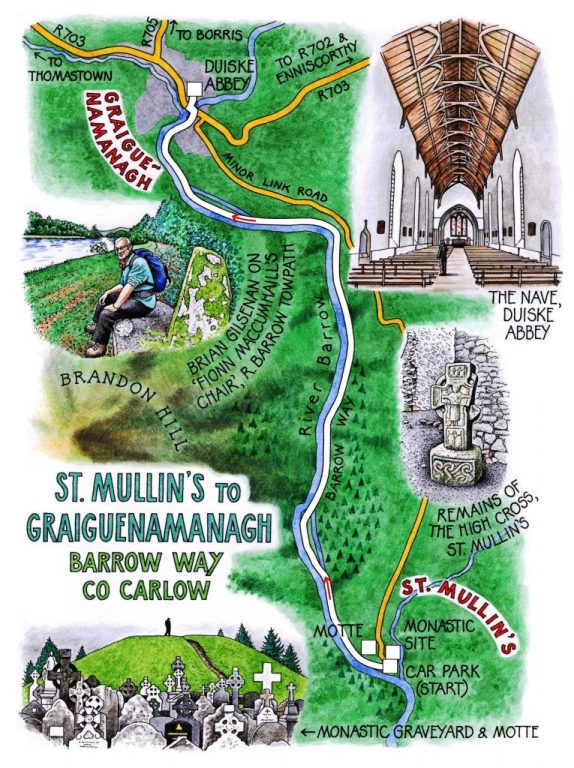

No 91: St Mullin’s to Graiguenamanagh (Barrow Way), Co. Carlow

The Norman lord who had a castle mound heaped up at St Mullin’s, and a wooden-walled and palisaded keep erected on top, intended the fortification to overlook the tidal limit of the River Barrow just below – a great place to extract tolls – and to overawe the locals. Castle, palisade, lord and tollhouse are long gone; the locals remain, and so does the motte, like a green suet pudding on a well-mown plate of grass. It’s a fine place to scramble up for a panoramic view of the monastery founded by St Moling that made the name and fame of St Mullin’s for close on a thousand years.

Girdled tightly inside a stone perimeter wall, weathered stubs of monastic buildings rise from a sea of ornate graveslabs and crucifixes like ruins in a fable. St Mullin’s monastery is a remarkable sight, poignant in its death-like stillness and silence. Looking down from the flat-topped motte, Jane and I let our imaginations supply the drifting smoke, scurry of lay workers and pacing of monks, crowing of cocks, barking of dogs and tolling of the church bells.

St Moling’s long life spanned almost the whole of the 7th century AD. He was a remarkable man, quite unlike most of the hermits who founded those early monasteries, poorly educated men with fierce convictions in their heads and fish-scales in their beards. Moling was born a prince and ended up an archbishop. He was a poet and thinker, but also a man of his hands who dug his own mile-long mill race, ground corn for anyone who asked him, and ferried folk across the Barrow on a raft he built himself. He managed to negotiate the abolition of taxes that were crushing the local peasantry. Moling, in a word, was good with people.

The saint never knew the monastery’s handsome abbey church, the ornate High Cross with its broad-faced crucified Christ, or the Round Tower whose base stands alongside the abbey. All these post-date Moling by many centuries. But the memory of the ferryman prince, the cures he wrought and the good he did in his long life are still well remembered around St Mullin’s.

Jane and I spent an hour exploring the ruins. Then we went down to the River Barrow and turned upstream along the towpath, following the puddled track of the Barrow Way. The day was starting cloudy and thick, with drifting mist through the valley, so that the summit of Brandon Hill, when it appeared at last rolling free of the vapour beyond the river, seemed a slate-grey leviathan breaking clear of a level white sea. ‘Do not fish for salmon or sea trout,’ admonished the notice by the keeper’s cottage at St Mullin’s lock, a reminder that here, twenty long miles from the sea, the Barrow finally reaches its tidal limit. Short sections of canal bypass the weirs, complete with locks, white-tipped gates and neat lock-keepers’ cottages in immaculate little gardens.

A swiftly walking shape ahead on the path resolved itself into the trim, alert figure of Brian Gilsenan. We’d made friends on a Blackstairs ramble last year, and here he was coming down the Barrow to walk back to Graiguenamanagh with us.

The weirs across the Barrow roared and frothed, the copper-brown water moving with the implicit power of a big snake. The narrow grass causeway of the towpath separated the river and its overspill ditches where lichen-bearded hazels and willows stood up to their hips in swampy floodwater, a County Carlow version of the Everglades. A floody, half-drowned, misty landscape through which we tramped the bank upriver to Graiguenamanagh.

Beyond the beautiful old seven-arched bridge and partially restored warehouse quays of the town loomed the square bulk of Duiske Abbey. Forbidding from the outside, what a revelation within – a soaring interior, delicately carved embellishments, arches and columns so slender and fluted they seemed hardly fit for the purpose of holding up the great walls and the intricate, boat-like roof. Duiske, the greatest Cistercian monastery in Ireland in its heyday, wielded a temporal power of which the rustic monks at St Mullin’s could only have dreamed. Now both foundations stand in humility, the one roofless and empty, the other magnificently preserved, for walkers and wanderers to wonder at.

WAY TO GO

Map: OS of Ireland Discovery Sheet 68

Travel: R705 or R729 from Borris; R703 from Thomastown; R702 from Enniscorthy – all to Graiguenamanagh. Leave one car here; drive other car to St Mullin’s (minor road). Park in riverside car park below monastic site.

Walk: From car park, uphill to explore St Mullin’s and monastic site; return to car park; right along River Barrow towpath (‘Barrow Way’) for 4 miles to Graiguenamanagh.

Length: 4½ miles

Conditions: Level riverside path – can be wet and muddy.

Refreshments: In St Mullin’s, Blanchfields pub (051-24745) or Mullicháin Café by river (11-6 daily, closed Mondays). In Graiguenamanagh, Coffee On High café, High Street (059-972-5725)

Don’t miss

• Saint Mullin’s monastic site

• View of Brandon Hill from the riverbank

• Duiske Abbey, Graiguenamanagh

Barrow Way:

http://tcs.ireland.ie/dataland/TCSAttachments/311_TheBarrowWay.pdf

Guided Walks: Contact Brian Gilsenan (053-937-7828 or 086-838-6460; www.mosscottageireland.com).

WALKING in IRELAND: Walking tour operators, local walks including Discover Ireland’s National Loop Walks, walking festivals throughout Ireland: www.discoverireland.ie/walking.

Donegal Bluestack Walking Festival: 30th April-1 May (087-784-4803;

www.donegalwalkerswelcome.com)

Tinahely Trailwalking Festival, Co. Wicklow, May Bank Holiday 2011: www.tinahely.ie

NB New ‘Walk Safely’ leaflet (Mountaineering Ireland & Fáilte Ireland) from TICs or info@mountaineering.ie (01-625-1115); download from www.mountaineering.ie.

Information: TIC: Tullow Street, Carlow (059-91-31554; www.carlowtourism.com).

csomerville@independent.ie