On the hillside at the end of the valley road we turned round and round, spellbound, as Michael named the peaks and hollows of a stunning panorama.

Breakfast at Hanora’s Cottage — now that’s a god-like start to a misty day among the Comeragh Mountains. Is there a cosier centre of warmth and cheer in Co Waterford? When Mary Wall and her husband Seamus first came to live here in the Nire Valley in 1967, Hanora’s Cottage was just that, a little cottage of two rooms hardly altered since it was built for Seamus’s great-grandparents.

Seamus has sadly passed on, and Mary runs the much-extended and modernised house with her son Eoin and his wife Judith. But Hanora’s Cottage continues to burnish the lamp of hospitality, just as Seamus would have wished.

It was Michael Hickey who turned up at eight on the dot to take Jane and me walking in the mountains — a man of his hands (some of the beautiful woodwork in Hanora’s Cottage is of his crafting), and a man of the hills whom you would trust to take you there and lead you back through all winds and weathers.

On the hillside at the end of the valley road we turned round and round, spellbound, as Michael named the peaks and hollows of a stunning panorama for us — westward to the golden Galtees and darkly clouded Knockmealdowns across the border in Tipperary, south to the nearer Tooreen ridge with its component high corries of Coumfea, the Deer Hollow, and Curraghduff, the Black Moor that shelters the twin loughs of Sgilloge.

For 500 million years, the wind and rain, frost and sun have been slowly moulding these sandstone conglomerate mountains with their winking white chips of quartz. Michael pointed out standing stones and ancient burial barrows across the hillsides far below, and the talk turned to the long tide-like movements of time, the rise and fall of civilizations and of modes of burial and commemoration. “The eternal question we go on asking down the years,” mused Michael as he stared over the valley. “Why do we have to age? Why do we have to leave?”

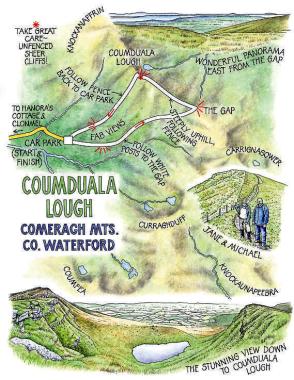

We followed a sedgy old green road, studded with stones and marked with white posts, eastward towards The Gap, a saddle of ground between Knockanaffrin, the Mass Hill, and Knockaunapeebra, the Little Hill of the Piper. Who was the piper? Michael didn’t know; but he did have a great saucy story of Fionn MacCumhaill and the women of Sliabh na mBan, at which we laughed like hyenas as we walked the track among sheep whose red flock-marks had run in the rain to dye their fleeces the campest of pinks.

From The Gap the view east was immense, way across Waterford and Kilkenny into Carlow and Wexford, wave upon wave of steel-blue hills floating in mist and running on towards Mount Leinster and the Blackstairs. “This is why I come out walking,” said Michael. “For me it’s a necessity. All my days I’ve had to be outside, walking these hills,” and he looked around like a man drawing in the very breath of life.

Turning our backs on this magical prospect at last, we forged steeply uphill over knolls and dips, by crusty outcrops of black rock. Mist began to swirl across, but with a fence as guide we were soon up on the spine of Knockanaffrin, balanced gingerly at the very rim of a scoop of sheer cliffs and looking down on Lough Coumduala lying 500 feet below, pear-shaped, with the muted gleam of a polished bronze mirror. Beyond rose the blue hills, each an island lapped by a river of mist.

Descending the steep breast of the Mass Hill, Michael Hickey flung out an arm to embrace Comeraghs, Galtees and Knockmealdowns. “If only people would lift their eyes from working 24 hours a day and look what’s there for the taking, they’d all be out walking.”