The forest track led us steadily uphill between dark walls of spruce, pine and fir. The information panels along the trail were excellent, a treasure-house of rural lore, natural history and geology.

“Bird life of Mount Hillary: the Golden Eagle,” suggests the signboard down in Banteer village. Now that might be a slight economy with the truth. Golden eagles haven’t been spotted over north Cork for the past century. But the noble king of the birds does at least still lend its name to the mountain, transliterated as ‘Hillary’: Cnoc an Fhiolair, or Eagle Mount, pride of the ancient barony of Duhallow.

Waiting for Jane and me at the trailhead above Banteer were Tim Ring of Irish Rural Development Duhallow, along with his two colleagues Danny Sheehan and John McCarthy. It was IRD Duhallow that set up three trails around the Coillte-owned woodlands on Mount Hillary, and it’s local people like Danny and John, under the auspices of the Rural Social Scheme who got out there with digger, sign boards and waymark posts to lay out the trails on the ground.

The RSS has around 2,600 participants all over Ireland, the three men told us as we climbed the forest roads — not just making hiking trails, but mending, painting, insulating and turning their hands-on skills to whatever needs doing. It’s a remarkable scheme, and not nearly enough celebrated.

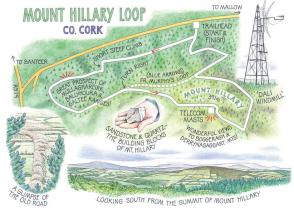

The forest track led us steadily uphill between dark walls of spruce, pine and fir. The information panels along the trail were excellent, a treasure-house of rural lore, natural history and geology. We learned of the folding of old red sandstone, of how young walkers could make a dreamcatcher from willow and feathers, of rowan-berry cures for gout, scurvy and the squitters. Magnificent views began to open northwards across the plains of Duhallow to the long grey backs of the Mullaghareirk, Ballyhoura and Galtee ranges out on the skyline.

From the top of a steep bank Danny pointed. “See the line of the old road?” It ran away across the land below, an ancient highway 30 yards wide between thick hedges, ice gleaming in the ruts, its purpose now forgotten. “They’d maybe have driven cattle up it,” hazarded Danny, “and over Mount Hillary to market in Cork or Macroom.”

These northerly Cork farmlands have always been good dairying and cattle-raising country. But recent policies and pressures have produced tough times for those who run traditional family farms. Danny’s is a dairying set-up, and he has seen prices for his milk fall to 20c a litre. John raises suckler cows on land that’s mostly bog, and he speaks of plummeting beef prices. Luckily, the RSS has been able to employ both men’s energy and practical talents.

Near the top of the trail Danny, John and Tim wished us well and went off about their own business. Jane and I forged on up a muddy track, to top out on the summit of Mount Hillary at 1,283ft (391m) among a clutter of telecommunications masts. A little apart stood a venerable prototype, its ladder rungs rotted, its wires drifting in the wind, skeletal and black.

A chill breeze out of the east nipped our cheeks as we sat in the heather and took in the southward view, a rolling sea of hill crests and slopes broken by the Boggeragh hills and the far-off mountains of Derrynasaggart.

It was one of those winter views that could hold you rooted for ever. There was no fairy music under the hill, though — just the melancholy pipe of the wind in the skeleton masts.