Irish Independent – WALK OF THE WEEK – Christopher Somerville

7 November 2009

‘Rosses is a little sea-dividing, sandy plain, covered with short grass, like a green table-cloth, and lying in the foam midway between the round cairn-headed Knocknarea and “Ben Bulben, famous for hawks”:

But for Ben Bulben and Knocknarea,

Many a poor sailor’d be cast away,

as the rhyme goes.’

That was the Rosses of Sligo as William Butler Yeats described them in The Celtic Twilight. W.B. knew a thing or two about rhymes, and he and his kid brother Jack certainly knew the Rosses, the sandy peninsula between Sligo Harbour and Drumcliff Bay, like the backs of their hands. Their mother Susan Pollexfen was a Sligo woman, and the Dublin-reared lads would often come to spend weeks at a time with their grandparents when money got tight. The wild shores around Sligo Bay, and the table-topped mountains of Benbulben and Knocknarea that were always in sight as landmarks from the coast, proved a life-long inspiration to the brothers.

Later in life, poet William and painter Jack would each acknowledge the ‘thought of Sligo’ that pervaded all their work. It was William who told the world about the Sligo legends of Knocknarea where rapacious Queen Medbh lies buried, and of Benbulben on whose slopes mighty Fionn MacCumhaill took a deadly revenge on his cuckolder Diarmuid. Jack, meanwhile, put ghosts and mysteries into the lonely strands and drifting figures of the Rosses with his loose, expressionist paintbrush.

On a windy morning of freckling drizzle, with more rain forecast from the sea, Jane and I struggled into wet weather gear on the seafront at Rosses Point. Niall Bruton’s haunting sculpture ‘Waiting on Shore’ stood facing the open Atlantic – a woman in wind-whipped skirts, her arms stretching seaward, archetype of the wives of Rosses fishermen down the ages. Her counterpoint the Metal Man, rigged out in 19th-century naval officer’s uniform, straddled offshore in the narrows opposite Deadman’s Point, his outflung arm pointing ships to the safe channel up to Sligo’s quays. Beyond man and woman rose the humpback of Knocknarea, the wild queen’s cairn standing proud on top under smoking cloud. Inland, though, Benbulben and its fellow mountains were hidden from the feet up.

Down on the long west-facing strand a few brave souls in billowing anoraks were battling the wind and spray. We strode out fast along the rain-pocked sands, boots crackling over dried ribbon weed, mussel shells and crab claws hollowed out by gulls, whose melancholy, whinging cries gave a bitter-sweet edge to the morning. Kidney vetch, harebells and tiny bushes of wild roses studded the dunes and low crumbly cliffs. Halfway along the beach, two surf-buggyists stood in contemplation of a giant dome of rusty cast iron, half-buried in the sand. ‘A boiler?’ one mused. ‘Or a buoy, d’you think?’ The other shook his long locks decisively. ‘Nope. A spaceship.’

Across the neck of the golf course we went, and down onto the long dune spit of the Low Rosses. Stars of insectivorous butterwort made lime-green rosettes in patches of sphagnum bog. The delicate silvery chrysalises of six-spot burnet moths were anchored to the stalks of marram grass, and the moths themselves in tar-black and crimson clung to the flowerheads of harebells and pyramidal orchids while they waited for the rain to die off. That wasn’t going to happen any time soon.

‘At the northern corner of Rosses,’ wrote William Yeats in The Celtic Twilight, ‘is a little promontory of rocks and sand and grass: a mournful, haunted place. Few countrymen would fall asleep under its low cliff, for he who sleeps here may wake ‘silly’, the Sidhe having carried off his soul. There is no more ready short-cut to the dim kingdom than this plovery headland.’

Out at the far point we lingered, looking across Drumcliff Bay towards Lissadell, delighting in the rainy solitude of time and place. Most poignant and beautiful of all Jack Yeats’s mystical late paintings, Leaving The Far Point has its setting out here. It must have been just this sort of weather – misty, windy and seething with sea rain – that Yeats had in mind when he shadowed out those figures of himself, his wife Cottie and Uncle George Pollexfen, as transparent as ghosts, walking the wet sands of Rosses Point on another wild day long ago.

WAY TO GO

MAP: OS of Ireland 1:50,000 Discovery 16

TRAVEL:

Rail (www.irishrail.ie) to Sligo. Bus (www.buseireann.ie): Service 473 from Sligo.

Road: N15 or N16 to Sligo; R291 to Rosses Point. By ‘Waiting On Shore’ statue, left to car park above lifeboat station.

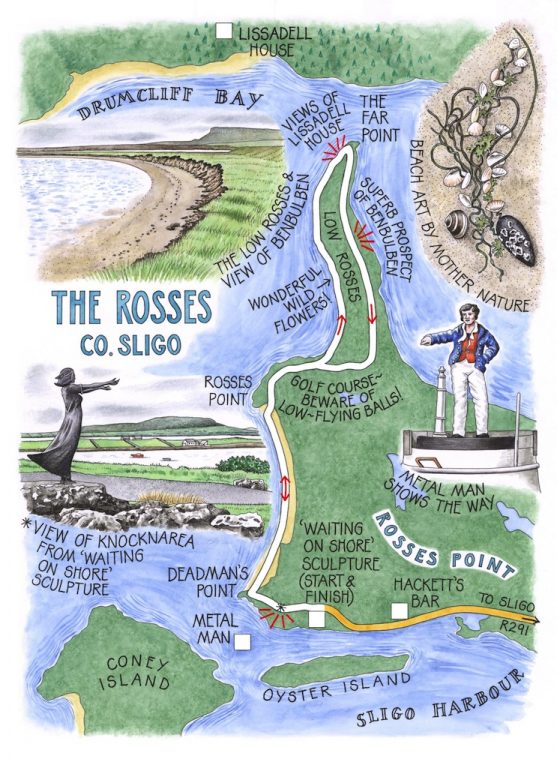

WALK DIRECTIONS: Follow tarred path towards sea; then follow cliff path and strand to Rosses Point. Cross side of golf course (watch out for flying balls!), keeping to cliff edge path. Continue clockwise around Low Rosses sandspit. Return across neck of spit to Rosses Point; retrace steps to car park.

LENGTH: 6 miles: allow 2-3 hours

GRADE: Easy

CONDITIONS: Cliff paths, sandy beach

DON’T MISS … !

• Metal Man and his Consort

• views of Knocknarea and Benbulben

• flowers of the Low Rosses

REFRESHMENTS: Hackett’s Bar on seafront, Rosses Point (071-917-7142)

JACK YEATS COLLECTION: Model Arts and Niland Gallery (www.modelart.ie), Sligo – closed for redevelopment; soon to re-open on The Mall, Sligo. Temporary contact: 071-914-1405. Paintings online:

http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/yeats_jack_b.html

INFORMATION: Walking tour operators, local walks including Discover Ireland’s National Loop Walks, walking festivals throughout Ireland: www.discoverireland.ie/walking; www.coillteoutdoors.ie

INFORMATION:

Tourist Office: Temple Street, Sligo (071-914-1905;

www.discoverireland.ie/northwest)

csomerville@independent.ie